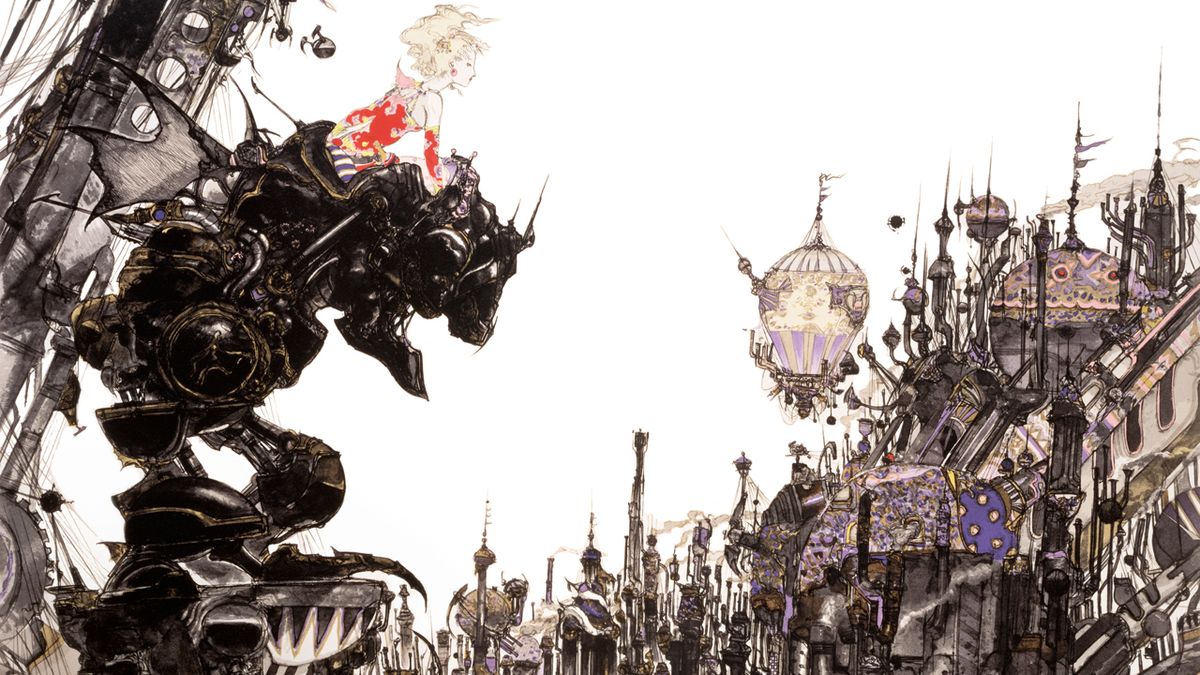

Final Fantasy III (VI) and its Amazing Instruction Booklet Illustrations

When I think of early fantasy video games, I think of two franchises: The Legend of Zelda and Final Fantasy. I'll talk about Zelda in another article, but this time I want to talk about Final Fantasy, and specifically about the SNES game, Final Fantasy III (now properly known as FFVI). I won't be discussing the gameplay or storyline. To be honest, I've never even finished the game‑‑-what with me not being much of a fan of JRPG gameplay. But what I absolutely love about FFIII is its concept art and opening title sequence.1 I'm not the first to talk about these elements of the game. The old SNES Mode 7 intro is famous, especially with those players of an age to remember when it first blew their minds in 1994.

What I want to talk about instead is the utterly 80s, David Bowie-esque, glam vibes this game's instruction booklet exudes. When you contrast the concept art that permeates the booklet, you can't help but notice the gulf between the 16-bit pixel art on screen with the high fashion illustrations appearing in the 80+ page (!) game manual. It's stark, and it's beautiful. What's more, for me, it's the concept art by Yoshitaka Amano that really lives in my brain to this day. Square may have retooled the video game, adulterated the updated versions with new graphics, but the original illustrations do more to create a sense of world-building, personality, time, and place than anything else associated with the game. For me personally, I'd say the concept art remains a touchstone of what fantasy can and should be given my preferences. That's the ultimate power of a handful of illustrations tied to the promise of a fully-fleshed world, even when you never finish the game.

What I love about this era of video games is the gulf between what developers were putting up on screen and what I can only assume is the vision the game writers and artists had in their heads. What I love even more, though, is that all these artists convinced their publishers to put some of what was in their heads into the various marketing and support material that accompanied their games. So it wasn't all just screenshots. It was concept art, commissioned illustrations, and backstory. And unless you only had the cartridge, you were nearly guaranteed to encounter all of these "alternate visions" for the game world. I can point to many, many Nintendo (original and Super) games that couldn't help but plaster fully-realized, hand-drawn artwork all over their manuals. For me as a kid just getting these games, I was both confused and delighted that the pixelated graphics on screen weren't the only window into the world being crafted by the game. It through me for a loop when an illustration didn't match the on-screen version. At the same time, I was able to eventually reconcile the different versions as just another take on the same character, enemy, location, or whatever. While I may have always thought of the on-screen graphical version as canonical, there was also a part of me that kept the separate, illustrated version in the back of my head‑‑-simultaneously holding both takes side-by-side. It was fun! And it triggered my imagination to go further. There wasn't one way to look at a character, but at least two. And if there were two, I knew, there could be more. It's as if the game's manual was giving everyone permission to create their own head canon, fan-fic vision of what they wanted the game to look like. It invited you into the world. It made the game, in an era when graphics simply couldn't do all the work, feel more alive and more akin to the respected genres of established art, like books and movies.

![]()

Still, in a few cases, I think a game's concept art manages to so far surpass what was represented on screen, that it took on a life of it's own more powerful (or at least more evocative) than the world I spent hours and hours staring at. Such is the case with FFIII. I know exactly what the on-screen representations of Terra and Locke look like, whether it was the small, full-body versions or the more detailed portraits on the character menu. Doesn't matter! What I really love all these years later‑‑-what really tugs at my imagination with a sense of untapped potential‑‑-is that damn instruction booklet. It's just so good! The version of FFIII that lives in those scant few drawings is the world I really want to leap into, but not so much the video game version.

All this leads to one question: why does the concept art tug at my imagination more than anything else related to the game? In part, it's Yoshitaka's line work and colorful, exuberant style. I'm a sucker for hand-drawn, rough around the edges, illustration. I love to see the hand of the artist in the final piece. I think, however, my fascination with FFIII specifically also something to do with the contrast between what is often a cutesy portrayal of the characters in almost chibi form (as presented in the game) and the very adult, glam form of the characters and art in the booklet. It's that more grown up vibe that captured my imagination, and still does today. It's an aesthetic, in other words, of reaching for something more complex than what you might be expecting from a 1990's era video game.

It evokes David Bowie in the movie Labyrinth‑‑-especially the scene where Sarah faces her unfamiliar, unnamed sexuality before she's really ready for it in the floating masquerade. The costumes are elaborate. The headware and hairstyles are prominent. Everyone is accessorized! It's all a bit extra, with a flair that evokes "fancy" just as a concept. And that's an interesting choice for a game set in a dirty, gritty world of steampunk fantasy. You think they'd want the characters to be as grimy as the setting, but no, the setting includes the characters‑‑-and the characters are a wish for something better. They stand out as little beacons of hope, the focus of the story, and they say that there was once something regal and hopeful in this world. Maybe there will be again. So with the costuming, the game designers hint at both character motivation as well as world history. Of course, it was also the style of the time. The illustrator in particular was known for drawing characters in all sorts of contexts with a similar style; but, here it works even better because of what it implies.

My point is that you can love aesthetics for the sheer joy of loving something beautiful. You can love them for the way they make you feel. You can also look at them as a window into what the art is invoking, and evoking. The aesthetics, in other words, does a lot of work that sometimes goes under-explored because we tend to focus on the pieces of a story, etc., that are more straightforward in making meaning. Aesthetics make meaning too, though! And we should all embrace them for all the many ways that a game like FFIII just "feels" right. There is enjoyment, which is valuable in and of itself, and there is also a level beyond enjoyment when the aesthetics match the art's message. I love it!

-

Yes, I will be referring to the game as Final Fantasy III (FFIII) throughout this articles. I know, I know! ‑‑- this isn't the preferred nomenclature today, but because I'm talking specifically about the original Super Nintendo of America package and manual, I feel I'm justified. The term FFVI simply encompasses too much these days, what with all the new versions, fan art, and remixes. Here I'm talking only about that very first American version of the game. ↩